Connor Thurston

Professor Siewers

ENLS 245 – Terror With a Human Face

9 May 2025

Demons: A Resistance to Totalitarianism

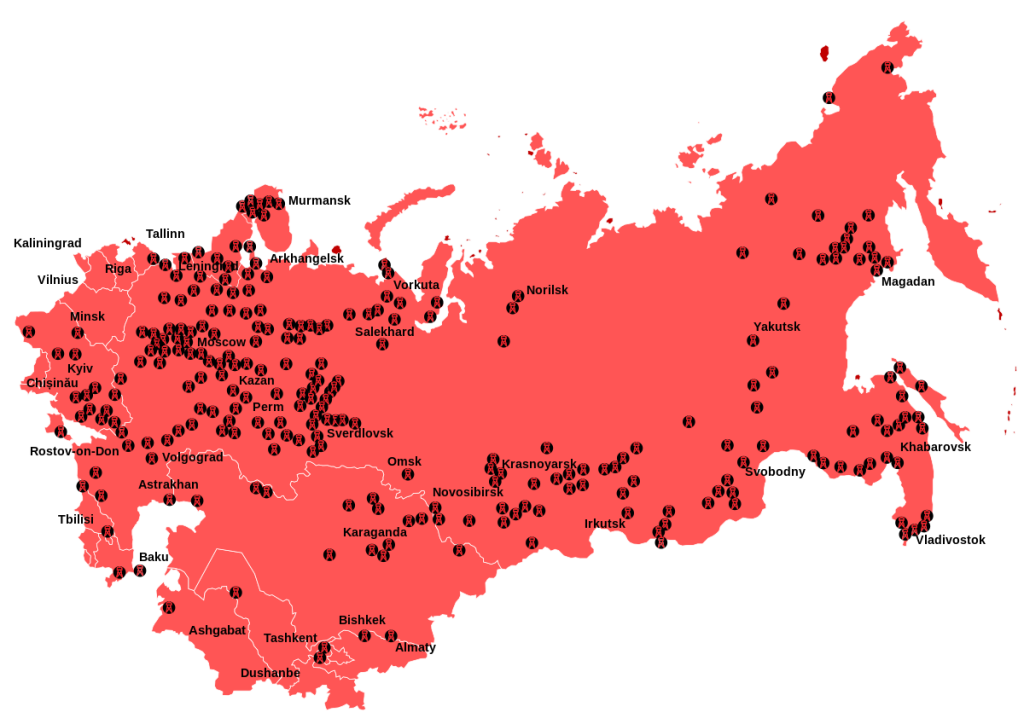

When Dostoevsky’s third novel was first published many critics claimed that the title of the English translation, The Possessed, was not accurate to its actual name in Russian. Bésy, which stands for Demons, was the name Dostoevsky and critics thought accurately represented the main message of the novel. The difference between these two names actively reflects the main message behind Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel, which uses the concept of demonic possession to highlight the dangers of surrendering individual moral judgment to radical ideologies, similar to how Hannah Arendt and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn both show why people subscribe to totalitarian ideologies which differ from their own personal views. Both authors in their respective works pull from precedent in totalitarian regimes in the real world to analyze why this behavior is so prevalent. In her novel Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt seeks to validate her idea of the “banality of evil,” and apply it to the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Solzhenitsyn, without formally expressing it, shows how Arendt’s term applies to Soviet Russian society by recounting the events leading up to and including his imprisonment in The Gulag Archipelago. Both author’s in their respective works warn about the implications that the banality of evil could have upon society, arguing that the key to uprooting this evil lies in understanding how totalitarian regimes drive people to commit terrible acts. While Dostoevsky’s novel takes place in a fictional town, the turmoil which takes place within the town accurately depicts the political climate of Russia in the late nineteenth century leading to revolution.

The political atmosphere of Demons is built up through extensive scenes of dialogue in the social circles of the upper echelon of Dostoevsky’s fictional town. The chapter “The Wise Serpent” details the arrival of two of the novels key characters, Pyotr Stepanovich Verkhovensky and Nikolai Vsevolodovich Stavrogin. Both characters show up to a gathering at Varvara Petrovna’s estate after being away from their hometown for a substantial amount of time. While their reason behind coming back to town is left unclear in this chapter, the reader can deduce that Pyotr is trying to reintegrate himself into the Petrovna’s social circle. It is revealed to the reader later that Pyotr Stepanovich is a radical revolutionary, and he has come to manipulate the townsfolk in order to spark a violent revolutionary uprising. Upon first arriving at the gathering, Pyotr immediately and successfully gains the favor of Varvara and the other guests. Eventually Pyotr shifts the conversation to Lebyadkin, in which he claims that Lebyadkin abuses his sister, Marya Timofeyevna, in order to extort money from Stavrogin. Upon hearing this claim, Lebyadkin tries to confront Pyotr, but he hesitates. “Pyotr Stepanovich seemed to be displeased with Mr. Lebyadkin’s hesitation; his face twitched in a sort of malicious content. ‘Perhaps do you want to make some declaration,’ he gave the captain a subtle glance. ‘Go right ahead we are waiting.’ ‘You yourself know, Pyotr Stepanovich, that I cannot declare anything.” (Dostoevsky 193). Later in the novel it is revealed that this is Pyotr’s claim is a lie, constructed by Pyotr in order to psychologically extort Lebyadkin into keeping quiet about Marya and Stavrogin’s secret marriage. This marriage is a secret that both Pyotr is using as leverage to establish power over Lebyadkin. Pyotr’s willingness to lie to and extort people like Lebyadkin is a reoccurring theme throughout the novel and speaks to the lengths that Pyotr will go to see that his revolutionary agenda is fulfilled. Pyotr’s justification for his actions mirrors the justification of totalitarian governments in silencing people and forcing them to conform to their ideas. In The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn comments that revolutionary movements in Russia justified their actions based on “Ideology – that is what gives evildoing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and other’s eyes, so that he won’t hear reproaches and curses but will receive praise and honors” (Dostoevsky 77). It is Pyotr’s ideological agenda which drives him to call out and extort Lebyadkin, exposing him as an abuser and wrapping him further in his plans for the town.

In the same way that Pyotr extorts Lebyadkin into silence, he also forces Lebyadkin into speaking against his personal thoughts. Instead of letting Lebyadkin sink away Pyotr hammers Lebyadkin with questions, refusing to let him leave the room until he has heard what he wants from him. “Allow me to leave, Pyotr Stepanovich,’ he said resolutely. ‘Not before you give me some answer to my first question: is everything I said true?” (Dostoevsky 191). Pyotr continues to toy with Lebyadkin, asking him if he is sober and if he recently threatened Stavrogin. All of these things are true, yet the context behind them is drastically different compared to what Pyotr is making it out to be. Eventually Pyotr threatens to reveal more about his family, and upon hearing this Lebyadkin gives Pyotr a crazed look. He then submits to Pyotr, saying “Pyotr Stepanovich, I am only now beginning to awaken!’ ‘Hm. and it’s I who have awakened you?’ ‘Yes, it’s you who have awakened me , and I’ve been sleeping for four years under a dark cloud. May I finally withdraw, Pyotr Stepanovich?” (Dostoevsky 194). Lebyadkin then hesitatingly leaves the room, looking as if he wanted to say something but ultimately thought against it. It is for fear of the Lebyadkin’s family honor that Lebyadkin gives in to Pyotr’s wishes and praises him when he originally wanted so badly to condemn him. Pyotr, as a radical revolutionary, hopes to get as many people on board with his ideology as possible. His metaphorical possession of others ranges from convincing people into revolution, to extorting people into praising him and wrapping them into his grand scheme for the future. Lebyadkin gives into Pyotr’s extortion partly because he values his family’s name and reputation. He sees Marya and Stavrogin’s marriage as a threat to his conformity into the town’s high society, so he praises Pyotr and gives into his coercion. A threat to conformity is a common tactic used in totalitarian governments to extort people into supporting their ideologies, which is similar to Arendt’s justification for the banality of evil. In conclusion to Eichmann and Jerusalem, Arendt states “That the ideal of ‘toughness,’ except, perhaps, for a few half-demented brutes, was nothing but a myth of self-deception, concealing a ruthless desire for conformity at any price, was revealed at the Nuremberg Trials, where the defendants accused and betrayed each other and assured the world that they ‘had always been against it’ or claimed, as Eichmann was to do, that their best qualities had been ‘abused’ by their superiors” (Arendt 175). This supports the idea that not all of the people who were involved with the Nazi regime harbored the same morally corrupt ideology which the defined themselves on. Some people did not oppose and even went along with Nazi ideology because they feared social isolation and persecution if they did not subscribe to their radical ideology, which mirrors the means by which Lebyadkin is coerced into supporting and even praising Pyotr. This makes Lebyadkin the first cog in Pyotr’s plan to spark a revolutionary movement amongst the town.

Throughout the course of the novel Pyotr slowly but surely wraps more people into his radical plans. He uses his father’s social connections to idealist revolutionaries to establish a group with the same radical ideology that he has, albeit with no plans of actually starting a revolution. In order to ensue chaos and destabilize the society within the town Pyotr is believed to have orchestrated many terrible events, including the incitement of a riot amongst the townspeople who burned down the governor’s house and the brutally murdered Lizaveta Nikolaevna. At this point in the novel Pyotr seems to have established a firm grip on the townsfolk built upon deception and deceit, but his possession is not as far reaching as he hoped. Pyotr realizes this when Ivan Pavlovich Shatov removes himself from Pyotr’s revolutionary circle and becomes more open about his transition into Orthodox Christianity. The fact that Shatov no longer believes in the revolutionary cause leads Pyotr to believe that he is a threat who knows too much and could expose the cell within the town. This leads Pyotr to plan and carry out his assassination. Before committing the assassination, Pyotr’s peers expresses a great deal of apprehension which Pyotr combats with threats and deception. “Even if they knock off two degrees for you legally, it’s still Siberia for each of you, and besides, there’s another sword you won’t escape. And that other sword is sharper than the government’s” (Dostoevsky 601). The metaphorical sword Pyotr refers to represent an individual’s sense of guilt. Pyotr weaponizes this guilt and uses it, combined with the threat of imprisonment, to further deceive and manipulate his cell into murdering Shatov in the name of his ideology. This manipulative tactic was the very same tactic used by NVKD in the Soviet Union, in which guilt would be implied upon arrest and was used as an efficient means to extract a confession out of a prisoner. When talking about the ways in which the NVKD would extract confessions from abductees, Solzhenitsyn writes “Intimidation was very widely used and very varied. It was often accompanied by enticement and promises, which were of course false… Intimidation worked beautifully on those who had not yet been arrested but simply received an officially summons to the Bolshoi Dom- the Big House… He would be ready to give all kinds of testimony and make all kinds of concessions in order to avoid these dangers” (Dostoevsky 46). Solzhenitsyn recalls stories about interrogations in which people are convinced that they can make their situation better, when in reality they are already set for the gulags. This same tactic of deception which throws guilt upon the accused is used by Pyotr in convincing his inner circle that Shatov needs to be silenced.

Although Pyotr was successfully in convincing Virginsky and Lyamshin into being a part of Shatov’s assassination, it is clear to the reader that they are not prepared to kill someone to protect their revolution in the same way Pyotr is. Once Shatov is dragged onto the grounds of the estate and shot by Pyotr, Virginsky and Lyamshin are sent into a frenzy, “But when the stones were tied on and Pyotr Stepanovich stood up, Virginsky suddenly started quivering all over, clasped his hands, and cried ruefully at the top of his voice: ‘This is not it, this is not it! No, this is not it at all!” (Dostoevsky 604). It is clear to the reader that they did not wish to kill Shatov, but none of them had the courage to stand up to Pyotr and voice their concerns. They are ideological cowards forced to acquiesce to Pyotr’s wishes in the name of his revolutionary ideology. In an attempt to rally the group together and remind them of their purpose, Pyotr say “You are called to renew the cause, which is decrepit and stinking from stagnation; keep that always before your eyes as encouragement. In the meantime your whole step is towards getting everything destroyed: both the state and its mortality. We alone will remain., having destined ourselves beforehand to assume power: we shall rally the smart ones to ourselves, and ride on the backs of the fools. You should not be embarrassed by it. This generation must be re-educated to make it worthy of freedom. There are still thousands of Shatovs ahead of us” (Dostoevsky 607). Pyotr seeks to reaffirm his justification for committing these terrible acts, bringing attention to the beautiful future in which these terrible actions will build. Pyotr’s need for justification in this moment is a human trait which Solzhenitsyn seeks to analyze in The Gulag Archipelago. In a sarcastic comment meant to mirror the Soviet’s though process in revolution, Solzhenitsyn writes “The result is what counts! It is important to forge a fighting party! And to seize power! And to hold on to power! And to remove all enemies! And to conqueror in pig iron and steel! And to launch rockets! And though for this industry and for these rockets it was necessary to sacrifice their way of life, and the integrity of the family, and the spiritual health of the people, and the very soul of our fields and forests and rivers– to hell with them! The result is what counts!” (Solzhenitsyn 307). Solzhenitsyn uses a sarcastic tone at many points throughout his novel to highlight the irony behind the soviet revolutionary mindset. Here he claims sarcastically that “The result is what counts” and yet he lists the many important things that the soviets have compromised in the name of totalitarian ideology. Pyotr similarly compromises the life of Shatov, one of his peers, and the solidarity of his revolutionary cell in order to further his plans in the town. Pyotr’s ideology is destructive not just for himself who genuinely believes in it, but for others who surrender their judgment and surrender to Pyotr’s cause.

While Dostoevsky believes that politically radical ideologies are destructive and dangerous, he also makes a considerable effort to show how the absence of ideology can lead someone to become destructive to those around them. Nikolai Stavrogin is a character who doesn’t believe or subscribe to any political ideology. He is not spiritual or religious and doesn’t have a moral code, instead being purely driven by a nihilistic ideology. Because he does not see a point or moral purpose to life, he is arguable the most destructive character in the story. Much of his character is explained in the originally omitted chapter of the novel, “At Tikhon,” in which it is revealed that he sexually assaulted and drove a young girl to suicide purely because it gave him a sense of superiority and pleasure. “Every extremely shameful, immeasurably humiliating, mean, and, above all, ridiculous position I have happened to get into in my life has always aroused in me, along with boundless wrath, and unbelievable pleasure” (Dostoevsky 693). What is most disturbing about this chapter is the lack of remorse that Stavrogin feels towards his actions. Instead he gains immense pleasure in doing things which other people deem unspeakable, which is something that Solzhenitsyn deems is at odds with human nature. “To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he is doing is good, or else that it’s a well-considered act of conformity to natural law. Fortunately, it is in the nature of the human being to seek a justification for his actions” (Solzhenitsyn 77). People seek justifications for their actions and in the case of Pyotr Stepanovich, the result outweighed the means. However the only thing that drives Stavrogin is a morbid, almost animalistic pleasure.

While Nihilism is referred to as an absence of moral ideology, it is important to mention that it is still ideology. It is an ideology which does not seek to justify the means by which it is achieved, and also accurately describes Pyotr’s radical political agenda. Stavrogin’s ideology is built upon an absence of religious faith and repentance. A key moment in which this becomes clear to the reader is when Tikhon seeks to turn Stavrogin towards Christianity. “You are in the grip of a desire for martyrdom and self-sacrifice; conquer this desire as well, set aside your pages and your intention– and then you will overcome everything. You will put to shame all your pride and your demon! You will win; you will attain freedom…” (Dostoevsky 712). Tikhon sees the self-destructive nature of ideological radicalism and tries to turn him onto a better path, and yet Stavrogin upon hearing his offer storms out of the monastery. His unwillingness to steer himself from his nihilistic ideology is inherited from his pride and ego, which reflects Pyotr’s devotion to his radical political ideology. Both characters seek to justify their actions through their extreme ideological views, and Dostoevsky shows the self-destructive nature of following their radicalism.

Demons is a novel which explores the dangers of subscribing to radical ideological values. Whether you are somebody who completely believes in this ideologies, or are somebody who uses it for personal gain, Dostoevsky makes it clear that there is no good that can come from ideas driven by violent revolution and nihilistic moral ambiguity. Arendt’s novel on Adolf Eichmann is key in explaining how totalitarian governments spread their radical thoughts into the minds of moral sound people. The idea of the banality of evil is extremely prevalent in Pyotr and Stavrogin’s followers throughout the book. While Lyamshin and Virginsky are not comfortable with murdering one of their friends, they stay silent as Pyotr shoots Shatov. Lebyadkin is forced both into silence and unwilful appraisal as he is being socially extorted by Pyotr. Stavrogin surrenders all moral judgement completely, not to any political ideology but to nihilism, which brings about the same self-destructive tendencies. Dostoevsky shows the reader the danger of being on each side of the ideological spectrum and both Solzhenitsyn and Arendt show how these ideologies grow amongst countries and eventually sprout into totalitarian regimes. Solzhenitsyn believes that recognizing what breeds people’s possession is key in understanding how to uproot evil from society. “We have to condemn publicly the very idea that some people have a right to repress others. In keeping silent about evil, in burying it so deep within us that no sign of it appears on the surface, we are implanting it, and it will rise up a thousandfold in the future” (Solzhenitsyn 81). Solzhenitsyn, Arendt, and Dostoevsky are authors who understand the meaning behind words. The Gulag Archipelago was a novel which was very influential in bringing the corrupt nature of the Soviet Union to the world and is often credited as a book which destroyed the USSR’s national reputation. In sharing these stories of political corruption and moral demise, Solzhenitsyn, Arendt, and Dostoevsky hoped to warn and prepare future generations about the dangerous of radicalism.